The history of chewing gum

From Neolithic birch resin to Mayan chicle and Greek mastic, explore the rich history of chewing gum and the medicinal uses of natural tree resins through the ages.

For more than 10,000 years, people worldwide have used tree sap resins, such as mastic gum, birch park, and pine, in their herbal remedies.1 Different cultures have valued these natural substances for their many health benefits, including supporting dental hygiene, relieving toothaches, aiding digestion, and promoting the healing of wounds.2 Additionally, the strong texture of these resins was used to support jaw strength and development.

The Sioux tribe in North America chewed spruce resin3, the Aztecs and Mayans preferred chicle resin4, and tribes in the Middle East and East Africa used Acacia resin5. Even Neolithic hunter-gatherers in Northern Europe left signs of chewing birch resin. These resins were prized for their toughness and antiseptic qualities, among other uses.6

Today’s variety of modern chewing gums can trace their origins back to these ancient practices of chewing natural tree saps.

However, most modern gums don’t provide the same health benefits as traditional gums like Mastic Gum, which are full of beneficial compounds and also free of added sugar. In the sections that follow, we’ll explore the fascinating history of chewing gum, a tradition that spans over 9,000 years.

The origins of chewing tree resin

The earliest evidence of chewed resin dates back more than 9,700 years to a hunter-gatherer community in Goteborg, located along the west coast of Scandinavia.1

Archaeologists found traces of birch bark resin on fragments of stone tools, suggesting it may have been used to help soothe a teenager’s toothache, possibly caused by severe gum disease. This is just one of the many uses of the resin noted by anthropologists.7

The analysis of this chewed resin has provided valuable insights into the oral health and dietary habits of Neolithic communities in Northern Europe. Researchers have discovered similar evidence of resin chewing throughout Neolithic Northern Europe, which may be attributed to the cold climate’s ability to preserve ancient remains. This could indicate that the practice was widespread among Stone Age cultures around the world.

How ancient cultures utilized gum

Throughout history, various ancient cultures have harnessed the benefits of natural gum resins for medicinal and recreational purposes. The Aztecs of Mexico, for instance, chewed chicle, a resin from the sapodilla tree, as a refreshing treat and to help with oral health.4

Similarly, indigenous tribes in North America, such as the Sioux and the Native Americans, used spruce tree resin for its antiseptic and healing properties.3

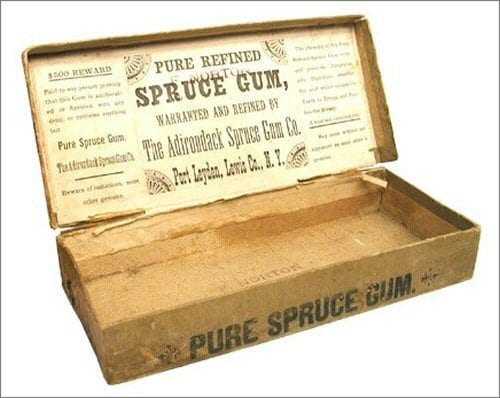

Spruce resin gum of the Amerindian Plains

Many Native American tribes, including the Lakota Sioux, commonly used pine resin as a form of chewing gum. This resin, sourced from the spruce tree, was harvested for both medicinal and recreational purposes.3

Spruce resin was especially valued for its anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving properties and was used to help soothe sore throats, joint pain, and respiratory problems. Spruce played a significant role in the development of modern chewing gum, as it was included in some of the earliest commercial gum varieties.

Copaiba resin gum of the Amazon Rainforest

Copaiba Resin, a thick amber-colored substance, is secreted from the Copaifera tree found in South America and Central America. It has long been a staple in the folk remedies of Indigenous Amazonian Tribes.8

Traditionally, these tribes chewed the resin and applied it to the body to treat infections, gastrointestinal issues, and various other health concerns. Additionally, it held spiritual significance for certain tribes, including the Yaviza people of Panama, who mixed the resin with honey and administered it to newborns in an attempt to ward off curses and impart wisdom.

Acacia resin gum of the African Savannahs

Commonly known as Gum Arabic, Acacia Resin is a light golden substance naturally secreted by the Acacia Tree.

Across various societies, from the Australian Outback to the deserts of the Middle East and the savannahs of Eastern Africa, Acacia gum was a prized chewing gum valued for its medicinal properties.5

Nilotic tribes, including the Maasai and Rendile, highly valued this resin for its numerous health benefits. Similar to other tree resins, it was used to relieve gastrointestinal discomfort, support oral health, promote wound healing, and address a variety of health concerns. Its resilience in harsh and low-precipitation climates made it particularly vital for communities that relied heavily on animal-based diets.

Chewing acacia resin helped people who ate lots of meat and animal products by reducing the risk of foodborne illnesses and poisoning due to decomposition in hot climates by purging potential pathogens from the digestive system.

Frankincense resin gum of Arabia

Frankincense is a natural resin excreted from the Boswellia tree that has been traditionally chewed for its potent anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, and analgesic properties.9 Frankincense has long been prized throughout the Middle East for its powerful medicinal properties, especially its potential to help treat and heal wounds and support recovery from respiratory ailments.9

In addition to its medicinal properties, Frankincense is linked to spiritual purification. Notably referenced in the Bible, Frankincense played a significant role in ancient Israelite Temple ceremonies and various religious rituals.

The introduction of mastic chewing gum

Mastic resin is excreted from mastic trees native to the Greek island of Chios, where it thrives in optimal conditions. The resin resembles a pale yellow crystalline teardrop and imparts a natural cedar-like pine cone aroma, especially when chewed.

For over 2,500 years, people have harvested and utilized mastic gum due to its remarkable healing properties. The earliest recorded mention of mastic gum dates back to Hippocrates, who recognized its potency as a medicinal therapy for gastrointestinal issues, toothaches, wound healing, breath freshening, and infection control.10

Throughout Mediterranean antiquity, it was a common remedy used by civilizations such as the Romans, Byzantines, and Ottoman Turks and shipped as far as China and India. Its medicinal value was so high that it was considered as precious as gold and was stored in heavily guarded chambers.11

The invention of modern chewing gum

The origins of modern chewing gum can be traced back to the Americas, where the indigenous practice of chewing unrefined spruce resin was widespread among both Native peoples and Colonial settlers.

By the late 1840s, innovations began to transform the gum production landscape. John B. Curtis was one of the pioneers in commercial chewing gum production, creating one of the first brands made from spruce tree resin. John Curtis led the effort to refine spruce resin into the first commercial chewing gum, which he made by boiling the resin, coating it with corn starch to prevent sticking, and making it more pliable for easier chewing.12

Chicle resin was also used for similar purposes. However, a decline in the availability of natural resin resources led gum manufacturers to pivot toward synthetic bases like petroleum, wax, and rubber, along with other artificial ingredients, which could be used to make gum chiclets.

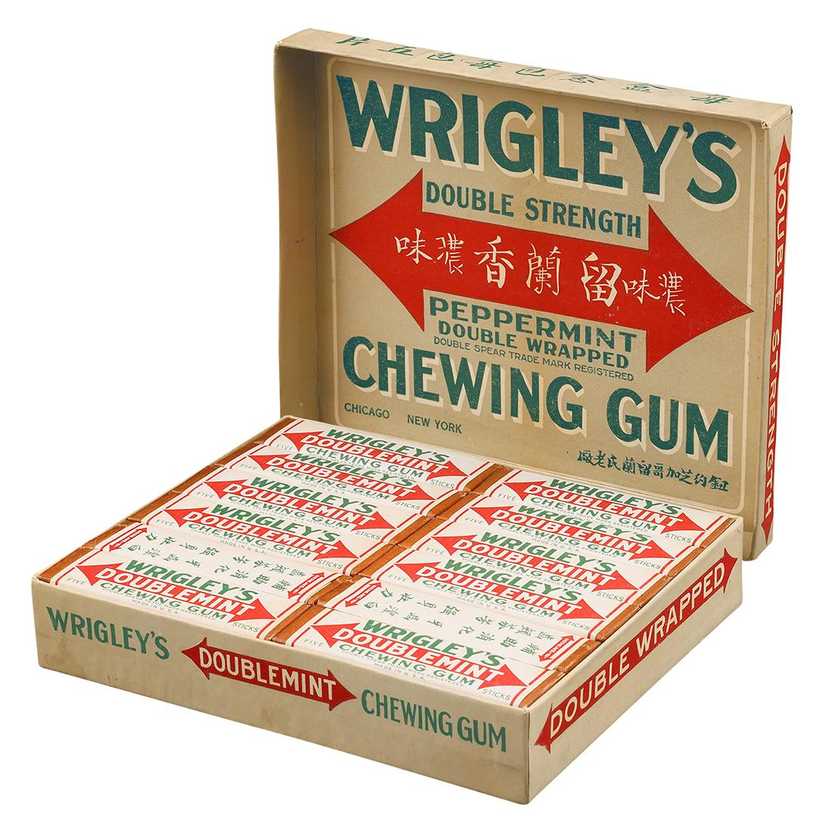

The lower production costs associated with these synthetic materials further accelerated this shift within the modern “bubble gum” industry. Popular varieties like Juicy Fruit and Wrigley’s Spearmint showcase the evolution of flavors in chewing gum, appealing to a wide range of consumers who care mostly about taste, with little concern for additives and sweeteners.

Downsides to today’s commercial gums

Modern chewing gum has evolved into a highly successful commercial product, celebrated for its convenience and portability. Through extensive artificial processing, gum has become soft, stretchy, and elastic, enhancing the chewing experience and allowing for easy packaging. The gum base used in modern chewing gum is often a blend of synthetic materials, including paraffin wax, which helps create a smooth and elastic texture, although this comes with drawbacks.

In the quest for cheaper, more accessible chewing gum and greater profit margins, today’s gums have lost many of the original benefits associated with chewing natural resins. The healing properties that once made natural resin gum, such as mastic gum, a health-promoting staple, have been largely stripped away from contemporary varieties. Chewing gum has shifted from a valued traditional remedy to a mere recreational activity focused on freshening breath.

Additionally, the softer texture of modern gum does not provide the mechanical tension needed to promote healthy jaw development and bone structure, inadvertently contributing to a decline in facial aesthetics and airway health over generations.13 Concerns have even been raised by experts like John Mew, considered by some to be the father of orthotropics, who urged gum manufacturers to consider creating tougher chewing options to support facial development.

Moreover, the incorporation of artificial ingredients into gum—such as petroleum, wax, and rubber—has introduced potential health risks, including microplastic contamination within the body. These materials not only pose unknown biological risks but also detract from the natural benefits once associated with chewing gum.

Finally, added sugars and sugar alcohols in modern gums have been linked to potential adverse dental health outcomes and gastrointestinal issues, raising further concerns about the impact of today’s gum on our health.

How mastic gum has stood the test of time

Reflecting on the history of chewing gum shows that while modern innovations have increased convenience, they have also diminished the valuable qualities of natural resins like mastic gum.

Once cherished by ancient civilizations and indigenous tribes for their medicinal properties, these tree bark resins, which are naturally sugar-free, have largely faded from common use, replaced by cheap, sugary, artificially produced gums that do little more than temporarily freshen your breath.

The shift away from natural gum resins is an example of the impact of industrialization and modern farming practices on our health and food supply. Reviving interest in traditional remedies like mastic gum can help us reclaim health advantages that were once integral to our diets.

This article originally appeared online in 2024; it was most recently updated on November 20, 2024, to include current information.

References

Footnotes

-

Kashuba, N., Kırdök, E., Damlien, H. et al. “Ancient DNA from mastics solidifies connection between material culture and genetics of mesolithic hunter–gatherers in Scandinavia.” Commun Biol 2, 185 (2019). doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0399-1 ↩ ↩2

-

Shen, T., Li, G., Wang, X., Lou, H. “The genus Commiphora: A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 142, no. 2 (2012): 319-330. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.05.025 ↩

-

Black Elk, L. S. (1998). Culturally Important Plants of the Lakota (By W. D. Sr. Flying By & Sitting Bull College). PDF download. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Mathews, J. P. & Schultz, G. P. (2009). Chicle: The chewing gum of the Americas, from the ancient Maya to William Wrigley. University of Arizona Press. Google Books ↩ ↩2

-

Ashour, M. A., Fatima, W., Imran, M., Ghoneim, M. M., Alshehri, S., & Shakeel, F. (2022). “A Review on the Main Phytoconstituents, Traditional Uses, Inventions, and Patent Literature of Gum Arabic Emphasizing Acacia seyal.” Molecules 27(4), 1171. doi: 10.3390/molecules27041171. ↩ ↩2

-

Fiegl, A. (2024, April 1). A brief history of chewing gum. Smithsonian Magazine. Link. ↩

-

Sheikh, K. (2019, December 17). What a 5,700-Year-Old Wad of Chewed Gum Reveals About Ancient People and Their Bacteria. Link. ↩

-

da Silva Medeiros, R., Vieira, G. “Sustainability of extraction and production of copaiba (Copaifera multijuga Hayne) oleoresin in Manaus, AM, Brazil.” Forest Ecology and Management 256, no. 3 (2008): 282-288. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2008.04.041. ↩

-

Hamidpour, R., Hamidpour, S., Hamidpour, M., & Shahlari, M. (2013). “Frankincense (乳香 rǔ xiāng; boswellia species): from the selection of traditional applications to the novel phytotherapy for the prevention and treatment of serious diseases.” Journal of traditional and complementary medicine, 3(4), 221–226. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.119723. ↩ ↩2

-

Soulaidopoulos, S., Tsiogka, A., Chrysohoou, C., Lazarou, E., Aznaouridis, K., Doundoulakis, I., Tyrovola, D., Tousoulis, D., Tsioufis, K., Vlachopoulos, C., & Lazaros, G. (2022). “Overview of Chios Mastic Gum (Pistacia lentiscus) Effects on Human Health.” Nutrients, 14(3), 590. doi: 10.3390/nu14030590. ↩

-

Torolsan, B. (2017, May). “Man, Myth and Mastic.” Cornucopia Magazine, 55. Online article. ↩

-

Little, G. T. (1909). “Genealogical and family history of the state of Maine” (Vol. 2, p. 526). Lewis Historical Pub. Co. Digital version. ↩

-

Mew, J. “Reading the face.” In The cause and cure of malocclusion. PDF download. ↩

Mastic gum is naturally hard and may damage dental work like fillings, crowns, or braces. By purchasing or using our product, you accept full responsibility for any dental issues or injuries that may result. Greco Gum is not liable for any such damage or harm.